Aziz Ansari and Dave Chappelle at the Paramount Theatre

“Burt Reynolds died,” I said.

“Well, we have no way of finding out,” replied the red gentleman in the PFG shirt, carrying a cocktail in a plastic cup into the restroom. “We’re useless.”

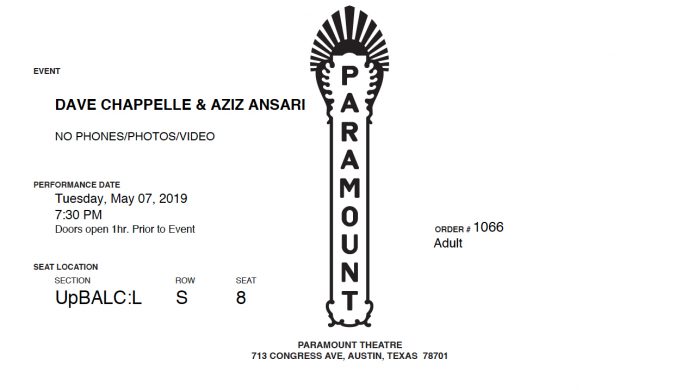

Our phones had all been locked away in little black pouches to prevent us from recording, broadcasting, or otherwise sharing any part of the event. Comics go to great lengths, these days, to make sure you’re not on your phone.

“I’m going to look this up later, and if Burt Reynolds is still alive, I’m going to be furious.” We all had a chuckle. We’re all comedians in line for the toilet at a comedy show.

The Paramount Theater was built in Austin, Texas in 1915. One of a precious few remaining examples of a classic Vaudevillian structure, it’s a gorgeous venue, resplendent with its ornate proscenium, its box seats, its balconies and mezzanines. Its tiny chairs, even, designed to accommodate smaller people from an earlier time. Not super comfortable to sit in now. But an appropriate scene, all things considered. A place of historical significance where, on May 7, two comedy legends grappled, each in his own way, with the same questions:

What does it mean to perform stand up comedy in 2019? And how does one go about it?

Aziz Ansari was, in his own words, coming off a “tricky year.” One in which his career was nearly felled by #MeToo allegations.

He started his set by talking about it. Not in explicit detail. But in terms of how he felt. He talked about how humiliated he was. How sorry he was that he had made another person feel so uncomfortable. You could sense him searching for the words to explain how terrible he felt, while not characterizing himself as the victim. He talked about how, ultimately, his feelings didn’t actually matter. The shifting paradigm was bigger than him, by a lot. Bigger than Master of None, bigger than Parks and Rec. What was important was what was happening, not how he felt about it. Which is a difficult position for a person who talks about his feelings, publicly and professionally, to find himself in.

“Not the most hilarious way to open a comedy show, I know.”

Where does comedy happen? When are you watching it? When is it real?

It’s a comedian’s job to provide social satire, commentary that we, in our working lives, can’t. And, as such, comedians need a “safe place” to work on material. To test boundaries. So that the world at large won’t judge them unfairly, should they go too far, and should that go viral.

But when has the material reached its final form? At the end of a tour? On a big-budget special on HBO or Netflix? On a comedy album?

Tickets went on sale for Ansari and Chappelle’s three-night run at the Paramount about a week before they opened, with little in the way of advanced promotion. Nonetheless, 18,000 people vied for the opportunity to spend a couple of hundred dollars to see these two men perform. (Though, according to the audience itself, nobody in the front row actually did this. They all bought seats from Stubhub or some other third-party reseller.)

For all the luck, expense, and, really, work it took to see it, it certainly felt real. Like: if this isn’t the show, what is?

Maybe it was an effort to provide a safe space for artistic experimentation. Perhaps it was to ensure a more-engaged audience. It could be a ploy to discourage excessive photography. (I seem to recall that Aziz used to start his shows with a moment for everybody to take his picture before encouraging the audience to put their phones away.)

Whatever the reason, we all locked our phones into the YONDR pouches. I told my mother, at home watching my baby daughter, to call the Paramount in the event of an emergency.

If anybody needed a space safe from cell phones that night, it was Dave Chappelle.

But let’s get something out of the way.

I don’t want to write a teardown. A hit piece. I love Dave Chappelle. He’s my favorite comedian. Maybe my favorite public figure. So many times — his turn as the first SNL host after the 2016 election comes to mind — his has seemed to be the only reasonable voice in the “room” that is popular discourse.

One of my fondest moviegoing memories ever was watching him introduce The Fugees at his Block Party. “Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for a miracle,” he said. It was exhilarating.

The best performance, play, musical concert, or otherwise I have ever seen was Dave Chappelle at the Moody Theater. He was transcendent. A master in his element.

I’ve even met him. Or, at least, I’ve been near him. After Chappelle’s Show ended, after he went to Africa and came back, when he had retreated from public view and had not yet reemerged, I saw Dave Chappelle riding a dirt bike-style motorcycle through a mixed-used retail district I was working in at the time.

“I have just seen a unicorn,” I texted a friend.

Later, he came into the store I was working at and bought some clothes with a credit card featuring the Chappelle’s Show logo.

“Should you … have this?,” my coworker silently wondered, ringing him up.

Insofar as I can love a person I don’t actually know, I love Dave Chappelle. But loving a comedian, in 2019, is a risky proposition.

First of all, they’re unreliable narrators.

When they talk about showing up in your town earlier that day, and tell you the story about the person they ran into on the street you recognize the name of, you can safely assume that they told that same story in the last town they were in.

In the case of Dave Chappelle’s set at the Paramount last Tuesday, however, I’m inclined to believe a lot of what he said. Or at least the part where he started his set by telling us that he had just taken “‘shrooms,” and that we had a limited time before things went off the rails. Which they very much did.

Example: At one point, much later in the show, he brought the evening’s emcee Wil Sylvince back onstage to read news items so that he, Chappelle, could provide improvised commentary. But, then, when presented a headline, Chappelle inexplicably responded by singing Prince’s “1999.” Which, to be fair, was very funny.

I don’t say this to snitch on my favorite comedian. If I’m honest, I mention it to provide cover.

If a comedian says something offensive, can we really take it that seriously if we accept that they’re (a) a comedian, and (b) on mind-altering drugs?

By contrast, Aziz’s hour was measured and controlled. Careful. He basically ended his set with a moment of mindfulness, the comedy equivalent of DMX leading the audience in prayer. It was nice to see, but the thoughtfulness definitely came at the expense of some laughter. Which is the central dilemma working comedians face today.

He spent a fair amount of time mining old bits for new laughs, recontextualized by the current State of Things.

‘These are the bits I would never do now,’ he was saying, but by bringing them up at all, he was able to nonetheless recycle problematic material. Less a call-back than an apophasis, and, certainly, one way to solve the puzzle.

Or maybe, maybe, it was a high-concept comedy experiment, whereby Ansari was merely testing the waters. Maybe, by dressing the wolves of his old material in the woolly cultural context and political atmosphere of 2019, he’s getting a clearer picture of what his audience actually wants. And if enough of them want the old stuff, then he can write new material without all the constraints of thoughtful consideration. This is almost certainly not the case. But in Austin, Texas, it sure seemed like the crowd preferred the less-sensitive material. But if I were to go into details, to give an example, then I’d be guilty of the same thing. You’ll have to take my word for it.

Another reason for the YONDR bags: comedy takes a long time to get right. If I were to share explicit details of the jokes in the show, even in written form, I’d be spoiling the show, and devaluing the material. Enforced cell phone bans protect the stand up’s chief commodity: the comedy itself.

One of Dave Chappelle’s moves, the kind of thing only he can pull off, and one of the reasons we love him so much, is that he can start with a controversial premise, then work his way back, walking the audience through his through his thought process, and arriving at a place of understanding, explanation, and hilarity.

Dave: Here’s a thing I think.

The Audience: Gasp!

Dave: But here’s why I think that.

The Audience: Ohhh, hahahahaha

And part of his charm is how easy he makes that seem. Effortless. Off-the-cuff. Intimate and personal. It almost seems like you could do what he does. But you can’t.

Chappelle creates the illusion of flatness, that he and the audience are on the same level.

They are not.

I remember an interview with Chappelle-collaborator Neal Brennan, who suggested — I’m paraphrasing — that Dave’s delivery and expertise comes from spending years being the smartest person in every room he was in, but being the only one who knew it.

So it was weird, and seemed rare, for a virtuoso like Dave Chappelle to introduce controversial statements without explaining them further.

“Louis CK didn’t do anything you could call the cops for,” he said, before jumping to another tangent altogether.

The problem with the #MeToo movement and the Women’s March? “Your movement is stupid.”

That kind of statement is one his fans might recognize as the introduction to a classic Dave Chappelle comedy bit. But he never developed either of them. They just died right there.

And then he started talking about the trans community.

Dave Chappelle has spent his career making fun of everybody. Every nationality, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and class. And until recently, everybody seemed okay with it. Because, again, it all seemed to come from a place of love for his fellow man. Until recently, he’s never dealt with any serious pushback from any of the communities he’s mocked. But now, faced with pushback from the trans community, Dave has dug in. His fixation on that community, on justifying his criticism of it, his material about it, borders on the pathological.

A generous interpretation of his preoccupation, one a fan might make, is that Dave is looking for a way in. Trying to find some kind of common ground that everybody, the trans community included, can laugh about together. And, given his track record, it’s an easy thing to want to believe.

But at his show on Tuesday, watching Chappelle flit from tangent to tangent, often returning to the “hilarious” plight of trans people, it didn’t feel that way.

If he’s going to stay on this issue, the trans community deserves Dave at his very best, at his most sensitive. At his most in love with humanity. But that’s not what they got.

The Dave Chappelle they got tried to close the show on a hopeful note of support for the trans community, who wanted to believe in the world they wanted, and who hoped he lived to see their dreams realized. But the lead up to that moment was bitter, mean, and reductive.

Even so, it feels like I’m letting Dave Chappelle off the hook. And maybe I am. Maybe he deserves the benefit of the doubt. Maybe not.

Who is stand up comedy for? And then who is it about?

If Aziz paid for his thoughtfulness with the laughs he might have otherwise gotten, and if Dave paid for the laughs he got by being insensitive, I don’t think we’re anywhere closer to figuring out how comedy is supposed to work in the here and now.

Maybe we laugh at Dave’s jokes because we sense a bit of ourselves in them. We feel seen. We feel known. And if the trans community — which can’t be fairly discussed, really, in these monolithic terms — doesn’t see itself in Dave’s work, then I think it’s fair to say that that’s a problem with the material, not with the community itself.

Maybe anything goes as long as everyone’s laughing. But what about when everyone else is laughing?

The day after the show, I called my sister on my way home from work.

“How was the show?,” she asked. She knew that I had been one of the lucky few to secure tickets directly from the Paramount site.

I told her all about it. How belabored Aziz’s set was. How wild and erratic Chappelle had been, how his unfinished bits had felt strange and cruel.

“That’s what 2019 is like,” she said. “People say all this terrible stuff, and we’re all just hoping there’s a punchline.”